Nothing in cart

The Military Watch That Forged a Living Collection

The Hamilton Khaki collection needs little introduction yet is entrenched in drawn-out years of history. The once wholly US’er brand has come a long way and has strong military bonds. Their pedigree espouses much more than their ties with Hollywood, where they’ve been sported on several individuals’ wrists in movies. The origin of the Hamilton military watch design is reputable, and they have unforgettable folklore among watch fans.

But little did we know these eminent timekeeping machines were born not out of curiosity but compliance to the American and Allies needs on the front line during the First and Second World War and beyond. As a result, a series of watches that provided outstanding reliability with accuracy was launched based on the US Army requirements. And since its birth, these Mil-spec watches have become synonymous with the brand, even with zero strings attached to movie screens or celebrities.

(Left: H69449861; Center: H64465733; Right: H64455533)

What attracted us to this “plain” three-hander watch with nothing but Arabic numerals and some luminance? Categorized by the utilitarian look and no-frills build that wraps around military personnel’s wrists, these functional pieces’ design has withstood time until today. With the first-ever purpose-built military timepiece introduced in the early twenties, Hamilton proudly rekindled the spirit of these adventurous and durable classic machines in the 1980s. Their meticulous approach gave its past traditional horology through the Khaki line not only a nod to their revivals, commemorating the historical design but extending the military baton into the future with a singular spirit. Their sporty tool watches are exemplary of their old-fashioned American spirit with Swiss precision.

As such, I thought we’d take this opportunity to look back at the origin, the beginning of the evolution of the Khaki collection – and how the brand has successfully kept an eye on its military roots. In this article, we will be focusing solely on the origins of Hamilton’s military patrimony, and hopefully in an extensive manner, so our readers can understand and appreciate the decades of effort that have gone into the Khaki watches over two centuries. From the Ally soldiers back then until today, when each of us can have the joy of owning one of our legacies.

Birth of the American Watchmaker

Before we begin following the amazing Khaki watches’ footsteps, we first need to take a considerable step back in history to learn the American watch brand’s birth. Things all started during the 19th century, the golden period for the US modern railroad industry. People used pocket watches to tell and synchronize time. While the importance of timekeeping was not fully realized, everyone knew that the railroad workers needed an accurate pocket watch to guide each freight journey in an orderly and timely fashion. This issue was somehow taken for granted, resulting in an ineluctable fatal accident in 1891. Known as the Great Kipton wreck on April 1, No.14, one mail train collided with another known as “ACCOMMODATION” at Kipton, a small station out west of Oberlin, the University town. This was due to one of the conductors forgetting to retrieve his pocket watch. It was then exacerbated when another fellow engineer’s watch stopped working for four minutes before running again.

Things escalated quickly into a disaster that killed both trains’ engineers and nine other clerks on board, with one forgetting to check the time and the other misreading it. As a result, the company hired a fellow Clevelander to investigate the incident. The man initiated a new set of standards for railroad pocket watches. Now, this story might be familiar to some of you. That’s because the fellow’s name was Webb C. Ball. Yes, the jeweler who started the Ball Watch Company we are all familiar with.

Conversely, what might be unfamiliar is that this tragic incident also spurred another American, Abram Bitner, a merchant from Lancaster, to develop reliable pocket watches for the railroad industry.

As a shareholder of an American watch company known as Adams and Perry Watch Company, Mr. Bitner had already been in the watchmaking scene since 1874. Two years later, he was appointed as the company manager and was part of another two newly formed companies by the same syndicate, known as the Lancaster, Pennysylvania Watch Company (August 1877 to October 1887). Later, the watch brand was established as Keystone Standard Watch Company (1886 to 1890).

As the then watch company wasn’t lucrative during those times, Mr. Bitner took this opportunity to buy out the majority shares in 1886. He established a newly named company six years later. The moniker was after a renowned Scottish-born attorney, Andrew Hamilton, who founded Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. This, along with the spur to make reliable portable timing instruments again for the railroad industry, helped establish the Hamilton Watch Company by Mr. Bitner and a new board of investors in 1892.

The inaugural of Hamilton might be lacking in gravitas due to an incoming dereliction. But the heroic move by Mr. Bitner would later prove fruitful as the watch company soldiered on through history, with considerable prowess in fabricating reliable timing instruments.

Refinement Came First

Another watchmaker known as Aurora Watch Company from Illinois was merged into Keystone Watch Company during that period. The acquisition allowed the gestate Hamilton to have the advantage in creating some incredibly reliable railroad pocket watches. It was possible because, back then, Aurora was a watchmaker with know-how, specializing in producing full plate movements that adapted to the requirements of Railway service back in the 1880s. Mr. Bitner’s Keystone was known for their robust “Dust Proof” designed watches covering the opening plate.

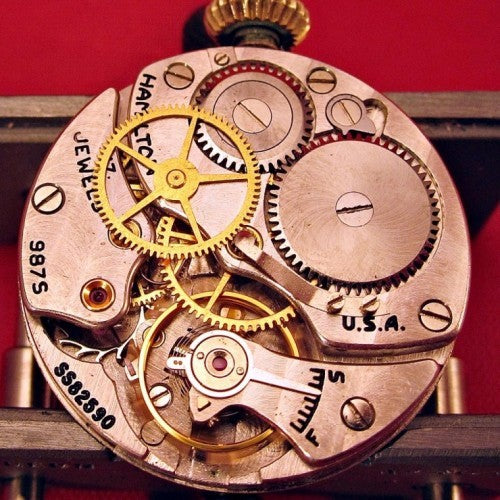

The collective efforts from both were merged into one, and Hamilton unveiled their first railway pocket watch in 1893. Designed as the Grade 936 for its movement – an 18-sized 3/4 plate pocket watch caliber that bears a total of 17 Jewels with double-roller escapement, Breguet hairspring, and an exclusive regulator. With that, the movement was painstakingly adjusted to five positions for accuracy, built to withstand temperature and isochronism factors. The dial was as impeccably executed as the movement, white enameling as the base, and large Arabic numerals painted on it. A sub-second dial was typical for a manual-winding movement back then and is placed right below, eschewing the 6 o’clock numeral.

Named the “Broadway,” this railroad-oriented pocket watch was well received in the railway watch market at that time; it even received plaudits as “The watch of the Railway” (sorry, Ball Watch). Vaunted for its accuracy and careful attention to detail paid by the watchmakers, which were later found in all Hamilton timepieces. From the late 19th and early 20th century, Hamilton produced two railway-grade pocket watches with their in-house movements for fifteen years. They boosted the company’s sales and helped them become widely known in the country as a master in watchmaking. During this period, Hamilton’s reliable pocket watches were already the official timepiece for all American Expeditionary Forces. They conspicuously had shown just how well-suited they were even for vigorous activities.

The Military Calling

When the world headed into the First World War in 1914, combatants needed equally reliable timekeepers to carry with them through the war, like those catered to railroads. Inevitably, notching a new set of challenges, WWI resulted in a need for a handier timepiece, compared to one that needed to be pulled out from the pocket. Therefore, the American watch industry adopted the use of pocket watches on the wrist.

More prominent local manufacturers like Waltham and Elgin had started producing these trench watches converted from large pocket watches. Through the soldering of wire lugs onto the sides of the case, readjusting the dial orientation, and pairing them with a leather strap, the trench watch was now able to be worn on soldiers’ wrists. From there, the watchmakers began tinkering to redesign their future watches, starting from scratch to make them more befitting.

Although Hamilton was not as nifty in operation capacity as the other two, they heeded to the war call. They were tasked with their fair share by issuing several trench watches since 1917. The first was based on the 983 movements that were initially found within ladies’ watches. Even though the movement was meant for the other half, a zero-sized ladies pocket watch movement allowed Hamilton to fabricate a more proportionate “wrist” watch for the fellow American troops in Europe.

As the trench watches were akin to both the land and aviation units, these esoteric watches also tend to be known as the “aviator watch.” And since Hamilton was still focusing on producing them in extremely high quality, only 1500 trench/aviator watches were made during the war period. This marked the beginning of the American watchmaker’s journey in manufacturing watches to be issued to the military.

Soon after the war, society began picking up with consumerism and lifestyle once again. In the early twenties, consumerism was heavily influenced by a classy quirk known as Art Deco—a movement on the rise. From futuristic architectures to transport and fashion, we can see that the style was even encapsulated in the world of watchmaking. Hamilton went on to purchase Illinois Watch Company – not just another pocket watch producer renowned in the railroad market, but also in the quirky dress watches of the 1920s. For Hamilton to pay attention to Art Deco dress watches that Illinois produced was almost a 180-degree turn. All the while, the watchmaker did not abandon their craft in tool watchmaking. From what used to be a practical design destined to serve the army, they expanded both their collection and target audience with their own Art Deco watches (later on under the Hamilton-Illinois branding in the fifties) through the acquisition enabled by Hamilton. Meanwhile, they continued the pursuit of pocket watch caliber development.

Now, you might ask why I have mentioned these non-affiliated aspects of Hamilton’s military watchmaking. It was a crucial move for inheriting the prowess of Illinois Watch Company by broadening the portfolio. It allowed Hamilton to introduce the first central “hacking” sweep second hand on a dressy model known as the Sentinel and Secometer. The hacking feature would, later on, be included in several military watches during the advent of World War II.

First There Were Marine Chronometers

Hamilton’s biggest claim to fame was the marine chronometer, which was an incredible achievement…” René Rondeau, vintage Hamilton expert and author of ‘The Watch Of The Future.

Things went on as usual until 1939 when the second World War broke out in Europe, and boy, this time, was Hamilton ever ready for the call of duty. Of course, the company was a natural choice to produce more timekeeping instruments for the armed forces. They had earned the credentials by supplying the military back in World War I. Hamilton’s patriotism was broadly displayed during this wartime period as they completely halted all production for the consumer market to focus on fabricating for the military.

Before we get to those iconic military wrist watches, Hamilton manufactured different timing instruments and timers with upgraded components. All that was seemingly unforeseen in the previous round but unquestionably impacted the next World War. This critical period allowed Hamilton to develop their own anti-magnetic hairspring alloy known as Elinvar Extra, followed by the development of new watch oils previously inaccessible due to the war. Notably, we need to pay particular attention to their production of precision marine chronometers.

Although the marine chronometers were invented way back in the 18th century by none other than John Harrison, Hamilton’s played a vital role in WWII. The portable timekeeper’s essential part was to provide celestial navigation in the sea back then when satellite GPS did not exist. It was used to determine the ship’s longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time and the precise time at the current location by observing the celestial bodies. Sophisticatedly, it imbued a gimbal system so that the pocket watch within was unaffected by the motions on board the ship.

With competent production capacity and avowed to solely focus on the war, the company could produce qualified marine chronometers for the US Navy and their fleets. When the government announced the commission of marine chronometers from all American watch companies, Hamilton was the only watchmaker able to mass-produce them to the strict Navy standards.

While Hamilton produced more than 10,000 of those navy marine chronometers, they had not only filled the numbers plainly but with meticulous effort. These accurate, robust chronometers performed so well that they were indispensable to the Allies from the start of the war up to their victory. Their users attested to them as an excellent instrument during wartime conditions. They were seen as an outstanding achievement for their makers. With that, the US Navy awarded Hamilton with the deserving “E” Award for their manufacturing excellence.

Second Call Of Duty

In 1942, Hamilton halted all consumer production to ensure we could supply the huge number of watches required by troops.

During this period, Hamilton and Elgin, Bulova, and Waltham had started producing proper military personnel wristwatches. This period is fascinating when we understand when the archetypical Khaki foundation was laid, which can be seen in today’s veraison. The US Army’s first requirement was to develop a watch for the infantry and air force – all based on the A-11 specifications laid down to all qualified American watchmakers at that time. The main tenets called for were the ability to hand wind, a hacking center second, also a 10-minute demarcation track on the rehaut.

Unfortunately, unable to compete in pricing with other producers after Hamilton’s submission (as Hamilton movements were manufactured more extensively at that time), only Elgin Bulova and Waltham offered the Type A-11. However, these mil-spec watches were not the only ones required, as Hamilton produced two others for the Allies. Throughout the war, Hamilton delivered more than one million watches, a significant increase from the previous round.

In 1940, the US Ordnance Department published a list of military watch requirements, including pocket watches, wristwatches, etc. This time around, Hamilton started producing their own, which featured the reliable 987A movement. Initially, the movement sat in a case-back snapped into place at the bezel, known as the Tea Cup style model. But due to lack of water resistance, Hamilton quickly upgraded the Model 987A with a dust-cover to protect the movement and inserted a gasket with a screw-down case-back for much better waterproofing. Both of which with “ORD DEPT USA” engravings on them.

Hamilton supplied these sub-second military watches mainly for the US infantry, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps, for six full years after 1942, with approximately 490,000 models of 987A made. They were reliable and trustworthy, clad with either a white or black Arabic numeral dial. The latter was mainly used by the Navy. Intriguingly, several of them even bore military branch-specific dials.

Remember I mentioned the improvement in mechanical components during this time? The 987A movement had an improved friction jeweling, alongside the Elinvar hairspring with monometallic balance. The ameliorated movement worked so well inside the watch that the Allies from Britain and Canada also equipped their pilots with these Hamilton watches. The Model 987A was considered to be accurate even under devastating changes in altitude.

“Gentlemen, Synchronize Your Watches”

Following the Model 987A, the consumer-oriented Hamilton repurposed themselves to pursue yet another essential watch catered to the Marines and Navy division. The conceptualization of the 987S movement now allows its 987 families to have a functional sweeping seconds hand in the center. During time setting, it hacks and reset at the 12’o clock position. These might seem like a norm, but the practice gave the troops a massive advantage in synchronizing critical operations during the war. This hackable, center sweep seconds movement was also used between 1941 to 1948, and appealingly during the pre-sixties Hamilton, around eight variants were clad with one within.

We all know that other manufacturers were churning a large amount of Type A-11 “hack” watches for the Allies at this point in time. Hamilton went on to focus their issued military pieces with their own hackable 987S caliber. Hamilton’s preeminent canteen dive watches for the US Navy were one such example. With the sobriquet based on its unique screw-cap design to protect the winding crown, recalling one from the canteen bottle of an infantry. The underwater purpose wristwatch was also known as the “BuShips” (engraved on screw-down back), which stands for the US Navy’s Bureau of Ships, established by the Congress on June 20 in 1940.

As stated, these 31mm unconventional canteen watches were mainly designed and issued to the personnel from USN’s Bureau of Ships and the Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDU) members, who were responsible for clearing harbors of obstructions at the wharves. Therefore, the canteen watch was ingeniously designed from the ground up to be waterproof at that time. Its unique properties like the screw-on cover over its crown, held in place with a small chain, along with its domed hesalite crystal soldered onto the top, and luminous markings and handset, preventing water ingression. On top of that, it aided the wearer with excellent unimpeded visibility. With the canteen divers, Hamilton and Elgin and Bulova were among the first few pioneers to engineer and develop one to befit underwater operations, with an unusual design yet robustly built to withstand the wartime activities. This particular version would later spur Hamilton’s modern take that it was heavily based on but with modern flamboyant flair, which we will get to later on.

Apart from the underwater-oriented divers, Hamilton had another exemplary reference. The R88-W-800 models were made and issued to the USN, Marine Corps, and the Air Force personnel. They were developed alongside their sub-dials variant with the same R88-W-800 Ordinance markings. The aesthetics basically shared the same case as the canteen divers, sans the cover cap replaced with a “big crown” for easier winding action. These watches had different engravings on the back, with the “FSSC/R 88-W-8000…” markings on their case-back. The dial variation was synonymous throughout production, along with the BuShips canteen divers – where they featured dust cover, rubber gasket, luminous handset, central sweeping seconds. They set atop on Arabic numerals featuring outer minute track, on either a black or white background.

Along the way, Hamilton had polished up the 987S caliber by adding on an extra jewel to the center bridge that supports the central second hand pinion. This allowed the movement to accoutre a better shock absorbent than the already robustly built 987 calibers. Consequently, both manual-winding movements were found in all Hamilton’s military wristwatches with the 88-W-800 Ordinance markings.

As it appears, the 2987 movement was known to be of the highest quality. And as such, it was strictly issued only in military timepieces during the war. Yet, these watches were in limited production, approximately 15,000 having been made. With the other issued wristwatches that imbued the 2987 and 987 calibers, Hamilton ceased their production for the Allies by 1948, which marked the end of their vital role in WWII.

That said, the American watchmaker, staunch in their support to meet the military needs, was far from allaying their production of military watches, which we will be discussing later on throughout the Post WWII period. As a matter of fact, after the tremendous effort seen during this hardship period, it might seem like it’s only a mark of an aflutter mantra of all things military-related.

Throughout the World War II period, we glean from Hamilton and the other local watchmakers their fervid essential roles for the US and their Allies. From just a few prominent timekeepers mentioned above, we can tell Hamilton’s production effort was no small feat. Hamilton had produced an array of timekeeping accouterments throughout the war for the Allies – they even went on to supply around 3000 model 987A for the Russian military and 2000 more Model 987S for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Evidently, wartime played a vital role in exemplifying Hamilton’s prowess and their capacity to contrive efflorescence in timing instruments for the military, coming into fullness conspicuously since the day the brand was founded forty-plus years back. At the same time, we gradually realized these military watches had significantly impacted Hamilton’s vision in watchmaking – influencing their upcoming field watches and some of what would be the watchmaker’s military effervescence after the second world war – as they became a legacy all on their own.

So What’s Next After World War II

By now, Hamilton’s watchmaking proficiency was revered by the US government. At the end of 1946, or should we say, the end of WWII, Hamilton Watch Company remained the state’s premier contractor to the military. In this section, we will pay close attention to what Hamilton offered from the 1950s through the 1970s, all in the context of their warfare journey. Within these two decades, Hamilton fervidly continued to supply several field watches, which paved the gateway to their assortment of sports collections later on, known to all of us as the “Khaki.”

The Korean War

To start the post-season off, we head straight back into yet another civil conflict, and that’s the Korean War, which began on June 25, 1950. During this three-year war, the US military was involved with and assisted the Republic of Korea’s Army. At peak strength, 261,000 Marines were installed in South Korea. This means that Hamilton continued to supply timepieces too. Since it was the Marine Corps deployed, the watchmaker issued the USMC an array of new watches to them strictly for their use only.

Now, at this point in time, the military had extensive inventories of watches on hand from the previous World War. Watch companies and the US government took the opportunity to re-case their previously chrome-plated wristwatches used in WWII into improved stainless-steel ones that were parkerized. They were marked on the back as “OF,” which stood for the Ordnance Department/Corps – for a 15 to 17 jewels waterproof wristwatch. And parkerizing, a chemical process of applying chemical phosphate conversion coating, further enhanced corrosion resistance on the steel surface.

While several were re-cased, Hamilton was proficient in upgrading theirs with a slightly more refined dial in white (for the Marine Corps) and a better movement known as the 747 caliber. The 747 caliber (23.2 mm) was slightly smaller than the 987A (24.8mm) yet equally reliable. Alongside the 748 version with the central sweep second, a successor of those 987S and 2987, primarily used within their other dress models.

While the company was busy supplying the Marine Corps in Korean War, the US military concurrently released the MIL-W-6433 specifications that resulted in Type A-17. First produced by Waltham, the Type A-17 was an upgrade from the WWII Type A-11, once made by the same watchmakers. Now the watch came with radium luminance on the hour numerals, 5-minute indices, and the handset, including the tip of the second hand.

What is so important to note is the placement of an auxiliary 24-hour track on the inner side of the hour markers to aid in reading military time. This, in particular, would be the rudiment of all military field watches to come after and was inclusive of Hamilton’s watches, which I will get to shortly. The Mil-spec timepieces were to be purveyed to the US Air Force. Several of them participated in the Korean War. By the late 1950s, the specification was once again upgraded to MIL-W-4633A, and the Type A-17A was introduced by Elgin and Bulova. They were basically still navigation-oriented watches but now had a parkerized case, just like that USMC Hamilton watches.

The Start of Modern Warfare

As we move into the post-World War period, we can see the US Government had relentlessly updated the mandated military watch specifications for American watch manufacturers to comply with. Apace with the Post mil-spec MIL-W4633/A, the US state published a different specification known as the MIL-W-3818 in 1952, with the “A” upgrade that came four years later. The 1956’s MIL-W-3818A spec had many criteria that consisted of different accuracy grades (I to III) and dial types and handsets (A to E). And since these new specified military wristwatches repleted other ranges, they were solely catered to the general US Army consumption for a broad range of general-purpose missions to precise special operations.

GG-W-13

Until now, you might have been wondering and muttering about why I would go through a whole list of a new stringent requirements by the state. It’s because all these new specifications are quintessential in paving the route for what would be the most notable Hamilton field watches yet to come, starting in the sixties.

The repute that kicked things off was the following update, known as the MIL-W-3818B in 1962. Its fundamentals were to be a general-purpose wristwatch with a 17 jewel movement (Hamilton’s forte) and to run within a daily rate of +/- 30 seconds, along with the hacking central second functionality. One skillful watchmaker that produced these was mainly New York’s Benrus. We take heed that Hamilton did not start creating theirs until the Mil-spec had grown to become the GG-W-13 ones in 1967.

Enter the GG-W-113. This particular mil-specs was one of the longest-running ones, which spread from June 6, 1967, to 1986. This generated specification detailed the military’s need for the most accurate and durable timepiece at that time, withstanding occurrences of actual combat situations and issued by the General Services Administration (GSA). Specifically, the GG-W-113 watches were produced by Hamilton, Benrus, Marathon, and Altus, distributed solely to the pilots that participated in world’s conflicts – like the late fifties Vietnam war and the Persian Gulf operations later on.

To sum up the requirement for these wristwatches, they are as listed below:

- A 15/17-jewel hand-winding moment

- Able to resist shock and survive a 4-feet drop onto a wooden block

- Daily accuracy of +/- 30 seconds

- Needs to be waterproof

- Luminous hands for readability at all times

- Needs to be anti-magnetic

- A hacking central seconds hand

- A minimum power reserve of 36 hours

With that, Hamilton met the requirements in 1967, producing their GG-W-113 watches through the quartz crisis period until 1986. Highlighting the process, the watchmaker first manufactured a classic black dial with the irreplaceable Arabic hour numerals that are flanged with 60-minute markers. These minute markers are partitioned into five minutes, each using a “dart-shaped” indicating the hour positions. The inner dial now conveyed the 24-hour auxiliary markings within the Arabic hour ones. This axiomatic trait carried over from the post-war MIL-W-6433 specifications.

The handset was now in the shape of a sword with a pointy tip and was applied with radioactive Tritium (Hydrogen 3), accompanied by the dart-shaped markers as well. All the elements had been clad within a matte 34mm parkerized stainless steel case. The watch was topped off with an hesalite domed crystal that would not shatter when upon impact. Regarding its movement, Hamilton introduced the adoption from Swiss counterparts. They had dominated during the forties as they’d flourished in their region. At the same time, the American watchmakers were caught up in the war.

Hamilton started importing Buren’s and Huguenin’s calibers in 1954, placing the 17-Jewel ETA caliber 2750, also known as caliber 649, within their GG-W-113 military pilot watches. The ETA 2750 was a reliable Swiss-made movement produced from 1969 to 1982 (just in time for Hamilton). It had a large balance with a higher beat rate of 21,600BPH for better accuracy, along with the famed Incabloc shock system and a longer mainspring that was responsible for its 50-hour power reserve.

With a renowned and prestigious movement like this, the GG-W-13 Hamilton’s was superior in terms of reliability and robustness. It was fitted with a Mil-spec NATO strap in nylon material on its fixed lugs for more remarkable sturdiness. The case-back bears markings of such: contract type, federal stock numbers, manufacturing part numbers, contract numbers, the manufacturing month and year, and lastly, the serial number of each.

You can now see the GG-W-113 traits that make it the most recognized version for watch enthusiasts—one of the uber military watches from Hamilton. So much so that the GG-W-113 and a prominent belated mils-spec inspired the brand to release modern versions of them in 2018, which we will get to later. But before we get on with 2018 successors, there’s one more particular variant that came as close to, if not equally, as recognizable as the GG-W-113 watches, and that’s the Mil-W-4637 specification models.

And MIL-W-4637

On October 30, 1964, three years before the release of GG-W-13, the US Government issued what might be a pivotal specification, at least for Hamilton, to replace the MIL-W-3818. If you ponder all these military specifications and are starting to get perplexed, this new update was known as the MIL-W-4637. The calling this time around was to produce an “expendable” field watch for the US military as their involvement in the Vietnam War was seemingly more significant. The main features of the 4637 as stated below:

- A general-purpose field watch that possessed a lower jeweled (not specified) for both quartz and mechanical movement

- Daily accuracy of +/- 60 seconds

- Designed to be “disposable”

- Case manufactured in either plastic or metal materials

- Dial format shares the same of MIL-W-3818B

Some of you might be baffled by the progression of the different numbering mil-specs systems up until now. This particular one would exacerbate things further as the MIL-W-4637 got several revisions throughout the years.

From revision A in September 1969 to revision G November 12, 1999. You would assume things could not get any more complicated. However, this particular spec would prove us wrong, as each revision still had its own different “Type,” with many more manufacturers participating in producing them. And during this post-World War epoch, the US government was more lenient on manufacturer’s design, resulting in plenty of them splodged with different case forms and dials. Therefore, for this dedicated article’s clarity, I will only be touching on the Hamilton’s.

Besides, Hamilton’s prevailing mil-specs were the GG-W-113 for the pilots, and the Mil-W-46374, which was for the “ground pounders”. Hamilton’s first lineup for the 46374 specs started from revision A lineup. The MIL-W-4637A type was mainly produced by Benrus, Hamilton, and Westclox.

Hamilton produced them in a 33mm parkerised stainless steel case and clad in the military dial synonymous with the GG-W-13, as they were all based in the MIL-W-3818B that came before them. From the case-back (see above), the “MFG PART NO 39988” connotes a 7-jewel hand-winding movement inside. And apart from adopting Swiss mechanical movements, the 7-jewel movement was known as “447 ST CO,” a German’s Durowe 7420/2 caliber. Produced from the largest German movement manufacturer at that time, Deutsche Uhrenrohwerke (or Durowe), provided this exclusive movement for Hamilton with a low jewel count and withheld plastic bearings for the balance – all that in the name of complying with the “expendable” criteria.

These revision A, general-purpose watches, were made in time for the Vietnam War, and swiftly on May 7, 1975, came revision B. Not much was changed, with the only addition being a radiation symbol with “Hydrogen 3” indication made compulsory on the dials. This was to indicate the use of tritium luminous paint now on the dial and hands.

They were produced this time around by Hamilton, Stocker and Yale, Marathon, and Timex with their plastic version. Although different manufacturers crafted their “ground pounder” in different shapes and materials, Hamilton remained committed to their traditional case-form, even after the end of the Vietnam War, and it lingers ever-so-long until this day.

The last revision that Hamilton participated in was more than a decade later, set by the US military on October 10, 1986. Intriguingly, the revision D compiled a total of five different “Types” of field watches, and each was as listed below:

Type 1: A minimum of 15 jewels mechanical movement with daily accuracy of +/- 30 seconds.

Type 2: A 7 jewel mechanical movement with daily accuracy of +/- 60 seconds.

Type 3: A daily accuracy +/- 7 seconds quartz movement, battery installed (the first for MIL-W-4637).

Type 4: Same as Type 3, with battery inside the box.

Type 5: Same as Type 3, battery not included.

While introducing the first quartz movement within the 4637 mil-spec, both Marathon and Stocker and Yale manufactured them. Still, Hamilton stuck to only mechanical ones here. Even better, Hamilton only produced the top echelon Type 1s throughout their final journey with the MIL-W-4367 specification.

Since it’s the Type 1 classification, the American watchmaker’s Mil-W-46374D version fixed on an unequivocal movement that most of us are familiar with in today’s time – and that is the ETA 2801-2. The Swiss movement was considered superior to all previous versions, including the caliber 649 (ETA 2750) used in the GG-W-13. First measuring at 25.6mm, it has a 17 jewel count and beats at a high frequency of 28,800BPH. Its reliability is undeniable and has been proven throughout the years. Even today, some of our manual-winding watches are still cladding.

Apart from the workhorse Swiss movement, the Type 1 Hamilton stayed true to its own preceding design – the sterile military dial placed within the fixed-lug bars parkerized steel case. This just shows how Hamilton, until now, had been providing technical supremacy with their watches for the US military, under the circumstances, by fulfilling all of the three different MIL-W-4367 revisions.

Out of the “disposable” team, the Type 1 from revision D was arguably the best among them. Its Swiss movement within was more than worthy of being a long-term prospect. All that said, little did any of us know that the release of Hamilton’s MIL-W-4367s would usher in a new watermark for durable performance that was seen as a departure from the disposable mentality. Many of these pieces still survive today and are sought after by military watch enthusiasts.

Before the late eighties, the sixties period saw the birth of a new phenomenon for Hamilton in military watchmaking. Together with the GG-W-113 coming in second, both the “Ground Pounders” and “Aviator” speak to Hamilton’s most iconic status and pronounced nature. More than any other genre from the brand, the MIL-W-4367, and GG-W-113 embraced irreverence with their utilitarian look that would spur the creation of the early field watches made available to the public. We all know them as the Khaki models, which became the most vaunted field watch design and tradition of all time that many of us could relate to.

A Rare Navigator Piece

Before we move on from here and into the post-nineties military field watches representing Hamilton’s Khaki of today, an exciting chapter Hamilton was the birth of Hamilton’s FAPD5101.

A direct cousin of the MIL-W-4367, the FAPD5101 design was similar but with a larger 36mm parkerized case. The watch was issued in late 1969 to early 1970 solely for use by the US Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force navigators (RAAF).

These can be considered the “big pilot” to boot at that time, powered by Hamilton’s caliber 684. The 17 jewel movement was based on the ETA 2391, an earlier iteration of the manual-winding Swiss caliber ETA 2801 architecture, appearing only within this military model. In comparison, this particular FAPD5101 version would be the rarest among all the production runs of these field watches.

The Other British Fellows

The second-rarest that was produced was explicitly issued to the British army. A tendril of the above classic field watches, one of the Blighty mechanical models, it was referred to as the “6BB” based on the W10 spec. Initially, the watch was supplied by local watchmakers like from Smith, Cabot Watch Company (CWC), with Hamilton being the American representative. The W10 nomenclature was regarded as a specific type of equipment for the Ministry Of Defence (MOD), with Hamilton’s known as the 6BB. These watches were produced between 1973 to 1976, with a low production volume.

Hamilton made them in an unconventional cushion-shape, defying the round ones that were the norm in the homeland. While unique, the case stays true to military styling with the inclusion of fixed lug bars, where a G10 Nato would be slipping through those and onto the wrist. The case was fabricated as a one-piece format, lending better water resistance with a lesser ingression point. The “skinny arrow” handset was befitting for the British military. The matte black dial featured a chemin de fer minute track on the periphery, with only Arabic-hour numerals within.

A symbolic link to the British spirit was the “broad arrow” emblem, which was printed at the bottom 6’o clock position, indicating one government property. Flipping the watch over, we could find the “6BB” designation along with the country code plus NATO stock number, and of course, the year of issue. Powered by the Hamilton 649 caliber, the W10 series shared the same movement as the GG-W-113 aviator watches.

Apart from the three-hander, another “6BB” was issued to the British Air Force. It was in the form of a dual-compax chronograph. As the MOD’s Defence Standardisation was altered for more commercially viable military pieces, Hamilton and three other manufacturers, including CWC, Newmark, and Precista, kitted the famed “Fab Four” chronographs that replaced the sixties Lemania Mono-pushers.

The Hamilton “Fab Four” Chrono was now powered by the workhorse Valjoux 7733 cam lever movement, which provided a running 60 seconds on the left sub-dial, reflected by a 30 minute counter on the other side. The dial resembled the three-hander “6BB”, like the broad arrowhead printed on the bottom of the dial, issued explicitly to the RAF division. It measured up on the larger side at 39mm with a similar specifications layout on the case-back, denoting that this model was a “6BB” chronograph.

Swiss Residential

Before we proceed further into modern-day Hamilton and their public-oriented military watches, I would like to share its transitional period. The American watchmaker shifted its operation to Switzerland.

It happened concurrently during the production period of their GG-W-13s when Hamilton acquired the Swiss manufacturer Buren in 1966. Both companies had operated in each country, where Buren provided several Swiss movements and Hamilton’s watches’ production, eliminating US production. Three years later, the company in Lancaster had entirely shifted to the Buren factory in Switzerland.

(Photo Credit: Empressissi)

However, things were relatively short-lived, and the Buren company returned to its roots with Swiss ownership in 1971. The same year, Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH), a collective horology specialist comprising brands like Omega and Tissot, purchased Hamilton’s watch division production to continue in Switzerland. The watchmaker forever is framed by the sister brand within the big Swiss group.

After that, Hamilton Watch became a lifelong Swiss manufacturer with an American background and continues to be part of the Swatch Group (after the merge of SSIH and ASUAG groups in 1984). Later in 2003, the manufacturing and offices were relocated to Biel, Switzerland, beside their elder brother Omega. In this case, we could safely concede that most of the military field watches were issued to home country America while some were thoroughly assembled in Hamilton’s new Swiss residential.